Who's Afraid of Michel Foucault?

Mitchell Dean and Daniel Zamora's book, The Last Man Takes LSD, mixes illuminating insight into Foucault's evolution with reductive political posturing. Why are we still having these arguments?

The Euro-American left, broadly conceived, has been mired in a series of interrelated, repetitive, reductive arguments since 1968. These vary in their key concepts and their attached evaluative terms—universal class politics vs. identity politics, culturally conservative patriarchal statism vs. dynamic inclusive horizontalism, serious collective organizing vs. lifestyle experiments. Pragmatism and idealism vary in their roles as claims or slams across these morphing debates. Each side is accused of becoming its other—class-based universalism begets the repressive police state, inclusive horizontalism becomes an arm of neoliberal capitalism.

In truth, these dangers of appropriation and distortion are real. Marxists can become Stalinists, and cultural radicals can end up promoting capitalist market culture. The problems with the repetitions of this tiresome debate lie with the reductive binary—with the tendency of each “side” to reduce the other to its worst manifestations, as if these were the inherent, inevitable result of the entire “tendency.” My interest here is in excavating the genuine disagreements, and disentangling them from the reductive smears. “We” on the broadly conceived left, are at a particularly vexing crossroads in the political present, and we are better equipped with the ability to engage rather than the pleasures of exiling our erstwhile opponents. The disagreements are real and consequential; the time wasting dismissals are costly.

I have been called a Stalinist (for defending some chavista strategies in Venezuela), a neoliberal apologist (for advocating queer feminist horizontalist social movements) and an ultra-leftist (for opposing marriage as state policy). In truth I am an eclectic leftist who draws from the political genealogies of communism, socialism, anarchism/syndicalism/horizontalism, feminism, queer critique, decolonial and indigenous thinking and lifeways. The through line is my commitment to anti-capitalist, egalitarian politics devoted to collective organizing for downward redistribution and dispersion of material resources, political power, and cultural freedom. I make my commitments in specific times and places, in contexts where the realization of the dream is conditioned by context—in terms of what Ernst Bloch via José Muñoz has called “concrete utopianism.”

The best way to illustrate the workings and impasses of reductive, binary debate on the left is through example. In the remainder of this post, I will examine marriage politics in the U.S., conflict on the left over the recent election in Ecuador, and the publication and reception of Mitchell Dean and Daniel Zamora’s recent book, The Last Man Takes LSD: Foucault and the End of Revolution (Verso, 2021).

1) U.S. Marriage Politics

From the 1990s through the Supreme Court decision legalizing “same sex” marriage in 2015, U.S. mainstream political debate focused on the liberal LGBT equality organizations vs. the conservative religious right. This focus obscured two other significant frames—the place of pro-marriage policy in welfare “reform” culminating in the 1996 Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act, and the bitter conflict between liberal LGBT and queer left formations over the political priority accorded to marriage equality.

The Clinton Administration’s successful effort to abolish “welfare entitlement” and replace it with temporary relief and workfare depended on the neoliberal assumption that human dependencies should be met within private households, and not via state social services like income support and child care. The argument was made in policy papers and political meetings that “the family” should be supported through the legal marital form. Needy women with children, who could not provide adequate support for their households, should get married and add a higher male wage to the household economy. It was clear to most policy makers that neoliberal rollbacks of the social safety net required the unpaid or low paid labor of women in households. That labor would supply child care, care for the sick and disabled, elder care and more. So “welfare reform” was paired with federal efforts to promote marriage—massive expenditures of federal money were invested in such programs for the poor. State recognized marriage has had many historical functions. But by the 1990s, marriage promotion was a key aspect of neoliberal social service erosion.

The “gay marriage” debate proceeded as if it was completely disconnected from marriage promotion in the neoliberal welfare reform context. Calls for “marriage equality” and “the freedom to marry” erased all the material functions of legal marriage in favor of focus on a single equality right. But a number of studies showed that the marriage right would benefit property owners most, and would not address the the most pressing needs of the majority of the LGBT population. And the first pro-marriage equality decision from the Massachusetts Supreme Court in 2003 clearly stated, in the text of the decision, that a fundamental function of expanding the marriage right is the prevention of dependency on state support.

Of course, marriage equality did and does extend crucial material as well as symbolic benefits to LGBT people. Access to partner health and retirement benefits, to family immigration rights, medical decision-making power and more. These are crucial, not at all trivial material concerns. But in every case the benefit depends on the role of marriage in state and corporate provisions. If health insurance and medical decision-making, immigration rights, social security benefits and more were not tied to legal marriage, the benefit would disappear. *As long as* marriage is privileged in state policy, marriage equality will be crucial for LGBT people as a bottom line access point. But wouldn’t universal health care, more open borders, etc make more sense? It is a function of the privileged status of legal marriage that LGBT equality organizations would call for marriage equality *and not* for single payer health care or open borders. The LGBT liberal equality camp was drawn into the neoliberal promotion of marriage rhetoric, at the same time that it was being used to justify the evisceration of the welfare state.

These arguments were heated between the equality camp and the queer left. Queer radicals called for a new agenda of universal healthcare, expanded public housing, the rights of immigrants (not just those married to US citizens), police abolition, and more—to replace the equality agenda of inclusion in marriage and the military. But oddly, the social democratic and revolutionary left in the US often advocated marriage equality as their LGBT position—a kind of add on, showing their commitment to inclusion. But they either were generally unaware of the existence of the queer (and feminist and anti-racist and well as anti-capitalist) critique of marriage, or they dismissed it as simply “ultra left.” Many dismissively described it as a kind of radical lifestyle posturing—as if politics were a performance of being too cool to marry. This was the same willfully distorting dismissal made by neoliberal LGBT equality advocates. There *were* (and are) some anti-marriage activists who are in fact just posturing. But the heart of the left critique of marriage under neoliberal conditions was/is an extension of the longstanding feminist materialist critique, itself in part derived from Friedrich Engels’ The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State. This left critique has nothing to do with “lifestyle,” and does not underpin an attack on people who get married (which is often not only beneficial but unfortunately necessary for a secure life). It constitutes a deep structural critique of the regulation of household and reproductive labor in relation to political economic formations.

Why does the non-queer left insist on ignoring or misrepresenting the queer left critique of marriage? For the same reasons that some portions of that left insist on equating the analysis of racial capitalism with multicultural corporate diversity politics, or reducing feminist intersectional material analysis like that contained in the Combahee River Statement to “identity politics.” These sections of the left routinely dismiss the deeper critiques of the relation of the structures of everyday life and intimacy, and the legacy of racial and settler colonialism, to contemporary neoliberal capitalism. They do this usually without reading the relevant work, or engaging the arguments. They simply sweep the whole thing under the rug of “anti-discrimination,” “recognition,” or “lifestyle.” Because there are in fact neoliberal versions of these more deeply structural material politics (my book Twilight of Equality is all about those evolutions and appropriations), it’s a fast and easy sleight of hand to move the focus and stakes to a location of easy attack and dismissal. And voila! Every political thinker and movement that does not conform to the version of universal class politics on offer is automatically neoliberal! This is the final move of Dean and Mitchell’s analysis of the political legacy of Michel Foucault (see below).

2) Election in Ecuador

Last spring I signed an open letter addressed to the editors of the socialist journals Monthly Review and Jacobin, complaining about their coverage of the 2021 election in Ecuador. The 200 signers of the letter are all aligned with left projects and formations. Our complaint was focused on the representation of the candidate of the Ecuadoran indigenous social movements, Yaku Pérez, and his political party Pachakutik, as a Trojan horse for the left’s most bitter enemies.

The election came on the heels of the unpopular government of Lenín Moreno, the successor to the decade-long dominance of Rafael Correa of the Alianza País. Moreno had moved substantially to the right of Correa’s leftwing socialist, anti-imperialist, anti-neoliberal government—an achievement of the “pink tide” in Latin America. But over time the Correa government’s reliance on extractivist practices for income generation, and their severe crackdown on dissenting social protest movements, hardened the opposition among anti-extractivist indigenous groups. Following the Moreno interregnum, the core binary political division between the Correa government and its neoliberal capitalist opponents, which had previously dominated the electoral landscape, was restored. But it was increasingly disrupted by the indigenous movement and its feminist, ecosocialist and queer components. The indigenous movement and its political party, while far from politically or ideologically monolithic, generated alternative visions for left governing, with alternative ecological conceptions of land and resource use along with visions of radically inclusive democracy. The first round of elections in February 2021 at first looked like it would result in a runoff between Correa’s candidate, Andrés Arauz, and the Pachakutik candidate, Yaku Pérez. But the surprising result was a runoff between Arauz and the neoliberal banker, Guillaume Lasso.

The conflict surrounding the runoff on the left was fierce. Pérez charged electoral fraud, and Pachakutik advised their supporters to spoil their ballots rather than vote for either of the two remaining candidates. Pérez has himself been assaulted, arrested and imprisoned for protest activity. The general criminalization of protest and the extension of extractivist policies by Correaists meant that an Arauz victory loomed as an existential threat to the existence of the indigenous movement. There could be no support for a neoliberal Lasso government either, but some Pérez supporters believed that a Lasso victory would keep them in the country and out of prison to fight another day, while an Arauz victory might wipe them out. This was a strategic gambit, not an ideological choice. But understandably the Arauz forces considered this position to constitute a profound betrayal of the overall left project. Not only Correa supporters specifically, but sections of the international left saw the failure of Pérez and his allies to support Arauz against a neoliberal banker as evidence of hidden neoliberal sympathies. Thus the Trojan horse charge.

The point of the open letter was to push back against that charge of betrayal of the left, to situate Pachakutik and Pérez in the contested space between two intolerable alternatives—neoliberal rule, and the dominance of a form of left statism that deploys police state tactics to suppress left opposition, in part in order to continue planet destroying extractivist practices. That space of opposition to both sides of the political polarity can feel strategically untenable, especially when the reaction of the repressive left is to view all opposition as neoliberal sabotage.

The dilemma of Ecuador’s election was reflective of our impasses on the global left. There is a history of left governments that turn to patriarchal repressive policing to maintain power, and to destructive environmental practices to generate income, often in the face of lethal global capitalist opposition. The felt need to centralize power and deploy military tactics develops in a context of genuine existential threat. From the Bolsheviks to Cuba or Venezuela and Ecuador, the sense of threat and the need for a powerful defense of the socialist project is real. Alongside these formations, various left social movements work to build alternative models of power that are cooperative, inclusive, democratic and anti-patriarchal as well as anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist. These formations can be disorganized, incoherent, and transient. Often, they are easily crushed by police power (e.g. the Paris Commune, Occupy). In the face of existential threat, they can seem like a distraction from the overwhelming task at hand—winning collective power against the forces of global capital.

But we can not remain trapped in a humanly intolerable binary of Correa vs. Lasso, ad infinitum. The only way to develop alternatives is to develop alternatives. When the left itself dismisses or even violently crushes those alternatives, we are left to face a future of repressive policing and/or human extinction on a dying planet. We can criticize Pérez and Pachakutik, and indeed many open letter signers disagree with many positions and decisions the movement and its leader made! But if left governments like Correa’s work to crush rather than engage and incorporate the creative forces of left social movements, if Pérez and company are left to face assault, jail or exile for their political thinking and organizing, what do we expect them/us to do? Like initially pro-Bolshevik Emma Goldman in the wake of the victory of the Russian revolution (which she celebrated), facing its subsequent evolution toward Stalinism, we are left in utter despair. You don’t have to be an anarchist to feel it.

One of the key features of the Marxist left attacks on Pérez et al is its patriarchal Eurocentrism. Indigenous thinking does not proceed from the dilemmas of Euro-America in 1968, or indeed from the Paris Commune through the Bolshevik revolution to the pink tide. The Eurocentrism of left binary thinking is strangling the political imagination of the left in the Global North. A deep engagement with the history of racial colonialism, with decolonial theory and practice, and with indigenous ways of thinking and living, accompanied by ecosocialist, feminist and queer strains within and alongside them, can help lead us out of the impasses of the entrenched binaries, the unwavering attachment to individual European male thinkers, the enmeshment in European histories, the dependence on extractivist economies. The rejection of this opportunity and challenge to engage could be fatal for us all. Which leads us into a consideration of Foucault……

3) The Last Man Takes LSD

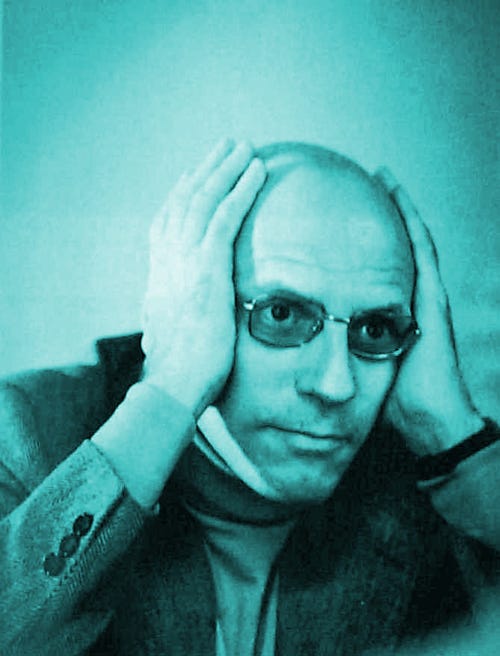

There is a variety of political theory and intellectual history that I always find frustrating—the kind that makes a leap from analyzing a thinker’s writing, to diagnosing political organizations and social movements as if they were derived from the texts that influenced them. Mitchell Dean and Daniel Zamora have produced just that kind of book in The Last Man Takes LSD: Foucault and the End of Revolution. It really is two books—a very illuminating history of Michel Foucault’s intellectual and political development in the wake of 1968 in France, and an annoyingly reductive analysis of his “legacy” in the present political moment.

Dean and Zamora place Foucault within the turmoil in Europe in the wake of the exposure of the brutality of Stalinism. Striving to find a “left governmentality” that would not reproduce authoritarian statism, Foucault was one of a phalanx of European thinkers struggling to rethink the building blocks of an egalitarian future without deeply embedded mechanisms of domination. He engaged deeply with a wide range of ideas, from the countercultures, the new social movements, the history of different forms of human relating, and the ideas of a newly emergent neoliberalism. He drew from the ancient Greeks, from the Islamic revolution in Iran, from Zen Buddhism, from German Ordoliberalism and American economics. In their account of Foucault’s search for experimental subjectivities and new intimacies that might shape the future, Dean and Zamora are quite careful to argue that Foucault was looking for resources not guidebooks—he seriously and deeply engaged but did not join the ancients, the Zen Buddhists, the neoliberals. Their account is solidly researched and engaging—I learned a lot about French debates on the left post-1968.

But then their analysis takes a sharp turn in the last chapters. They begin to reduce the complex history they have carefully crafted in a search for Foucault’s significance for us now. They flatten his experimental engagements, pointing to the resonance of some of his thinking with multicultural corporate diversity programs, with so-called identity politics and with the lifestyle focus of new age neoliberal wellness rhetoric, etc. Leave aside the fact that Foucault was the most trenchant critic of “identity politics” from his time to ours, and just note that this kind of move can be made with any complex evolving thinker. We can find in Marx the seeds of Stalinism, but we should not then conclude that Marxism inexorably leads to totalitarian statism. Why, if we can find in Foucault’s work some elements, some exclusions, some moments that resonate with the more progressive formations of neoliberal capitalism, are we justified in concluding that Foucault’s experiments in thinking led us to this? Here are Dean are Zamora:

“This complete redefinition of politics in terms of subjectivity must, however, be seen as a starting point for the production of a neoliberal Left more committed to equal opportunity and the respect of difference than to abolishing the exploitation of humans by other humans. ‘Don’t forget to invent your life,’ Foucault concluded in the early 1980s. Doesn’t that sound familiar to [neoliberal economist] Gary Becker’s injunction that we should not forget to be entrepreneurs of ourselves?'“ (169-170)

Well, no. These are not the same at all. I could point to how and why, line by line. But why bother? There are a wide variety of readings of Foucault, made more complicated by the inevitable distortions of translation—disagreements over interpretation are inevitable. The important question at stake concerns Foucault’s impact. The place on the current left where Foucault has had an enormous political (not solely intellectual) influence is not among the progressive neoliberals, but on the horizontalist left. These movements offer some very incisive critiques of Foucault’s thinking! His work is a resource, not a guidebook. The aspect of this thinking that seems to resonate most widely is Foucault’s insistence that, in order to reimagine the forms of power that contort our politics into modes of domination rather than sites of freedom, we need to rethink our ways of relating on the micro-level of intimacies and experiences. Only through this rethinking can we reinvent our institutions and collective decision-making and resource sharing in ways that don’t unself-consciously reproduce exploitation, repression, exclusion, stigma, misery. If we don’t reconsider the cultural contexts and dynamics of our intimate social relations, we can’t remake our political economies into supportive structures for human flourishing.

Dean and Zamora absolutely do not read Foucault this way. They see his focus on the art of the self, on intimacy and expression, as rejections of macro-level political economic thinking, rather than as the precondition for it. But the biggest mistake they make, in my view, is to try to tie current political developments to Foucault’s thinking in the first place. Neither contemporary Zombie neoliberalism, in either its soft/progressive or hard/reactionary forms, nor left horizontalist experimental politics, nor indigenous ecosocialism, owe much to Michel Foucault. Why these authors want to tie this thinker to such big swaths of a world that is no longer defined much by what goes on in Europe is quite beyond me. Which isn’t to say they aren’t illuminating about post 1968 Europe—they are! But extrapolating from there the train goes rather wildly off the track.

The very worst moves they make are trying to tie Foucault’s take on the Iranian revolution to the current rise of right wing populism, and their covertly homophobic assessment of Foucault’s “lifestyle.” Though they make some brilliant points about the role of political acclamation and affect drawing from Foucault’s observation of Iranian protests, they ultimately suggest that his appreciation of aspects of Islamist rallies and rhetoric signaled an opening for right wing populism in Europe and the U.S. The covert homophobia leaps out from start to finish, but is most apparent in the conclusion. From their emphasis, even in the title, on Foucault’s experiments with hallucinogenic drugs and his participation in the BDSM clubs of San Francisco, they go on to sling around the word “lifestyle politics” as a kind of diminishing smear masquerading as a description. In the end they insinuate that this is what his thinking amounts to in the end—navel gazing gay sex on drugs, enabled with some neoliberal personal “freedom,” that passes for politics. This is what a lot of homophobes think, but no queer people do. Queer sex has no inherent politics—it can be deployed with reactionary as well as progressive meanings, just as “the family” can. Though these authors make a number of patronizing gestures of approval for LGBT inclusion, etc., they clearly have read no queer or trans feminist theory, nor engaged at all with left queer political thinking and practice. The point in such thinking is: Reimagining forms of intimacy and sociality, along with reinventing the meanings of gender beyond the limits of the regulated relationships sanctioned by the state or celebrated and sold in the market (including gay ones), is a key component of transformative political life. Most queer leftists then go on to apply that to their critiques of capitalist labor relations, etc. Our work lives are a resource for thinking about modes of labor exploitation, and our intimate lives are a resource for imagining our way out of social domination. Foucault’s work is a resource too, an exceptionally rich as well as starkly limited resource—not a guidebook.

4) So what?

So why should anyone care about the Dean and Zamora take on Foucault? Because I think they reproduce the forms of sidelining and insult that many left decolonial queer feminist and indigenous horizontalist activists feel (I use this as an expansive umbrella term) within broader left contexts often dominated by social democratic and Marxist revolutionary contingents. We are not allowed to join the conversation. “We” read “their” work but they do not read ours.

*When I was a graduate student in the 1980s I went to a meeting of the Mid-Atlantic Radical Historians Organization in Philadelphia. My feminist comrades and I proposed that the reading group consider Gayle Rubin’s classic and massively influential article “Thinking Sex.” We were told, in condescending tones, that Rubin was not “Marxist enough” for this group to read. We all dropped out, wondering how the exclusions and oversimplifications of gender dynamics in Marxist thought and history could be redressed if we only read texts that were deemed Marxist enough?

*In my left leaning interdisciplinary department at NYU, all the graduate students are required to center categories of race and class in their work—this happens unevenly, of course. But only the students working with gender and sexuality faculty are expected to also examine those dynamics. In general, most of the gay male-identified students address gender and sexuality, and nearly all those identified as women do. But in my over 25 years at NYU, only a couple of straight cis male-identified students have produced dissertations that seriously analyze gender and sexuality in relation to their topic. Why is that? To even engage those analytics seems to mark students as female or queer—best for the others to remain superficial in their inclusions?

* I teach histories of political economy in relation to social formations. I have also been a longtime critic of neoliberal “identity politics.” I had a colleague who directed undergraduate students with any interest in race, gender or sexuality to me, noting that I could help them with “identity politics,” as he was more concerned with political economy.

*I was described at the meeting to vote on my tenure as a “lesbian community historian,” an absurd description of any of my work. When I began to try to avoid that kind of ghettoization, I wrote a book that did not use the words gay, lesbian or queer anywhere in the title or description—Twlight of Equality? But that book, though widely cited by queer and feminist scholars and activists, was not read much beyond those groups. I was already tagged and shelved.

There is so much more. But the more important context for the current shifting reception of Foucault (he has recently been accused of pedophilia, among other things) is the way he has been recruited, absurdly, as an avatar for “identity” or “lifestyle” politics, in the general effort to marginalize and diminish the writers and thinkers influenced by his work. This is happening exactly as the broad left faces an uncertain future of crisis and opportunity, as the neoliberal center appears to be collapsing and the far right is rising across the globe. The left needs to think about the scale of our organizing, the institutions and practices we deploy, the populations we speak to, in new ways. The “older” formations and languages still resonate, we can not understand the world we face without recourse to Marx and Marxism, to class and labor unionism, to the dynamics of empire and militarism rooted in devastating history of capitalism. But we need other resources as well, drawn from other geographies, populations, genealogies and practices. I am influenced by Fanon and Said, by Angela Davis and Robin Kelley, by Cedric Robinson and Glen Coulthard, by Emma Goldman and David Harvey, by the Combahee River Collective and Black Lives Matter, by Occupy and NoDAPL, by many overlapping threads of left thinking and organizing—in the interest of trying to find a way forward. Yes, that makes me an apostate to the comrades who feel a strong allegiance to a particular collection of genealogies. I am still getting pushed out of the contemporary versions of MARHO, all the time. But this feels like a big mistake to me; I keep trying to get back in the door. I belong to DSA, though my politics are somewhat to the left of most other members—which has a queer caucus! I go to socialist conferences and Queers and Against Israeli Apartheid meetings, I listen to anarchist radio, I read communist magazines. I keep trying to step out of the queer ghetto. The arguments in Dean and Zamora’s book, their flattening and diminishing versions of the left politics of others, keep pushing me back down and away. In a book otherwise so insightful about the political context surrounding Foucault’s work, this is dispiriting.

Note: I use these substack posts as a place to think out loud, to develop ideas and vent feelings that might gel into something more substantial later. These thoughts constitute a rough draft. I welcome comments sent to me at lisaduggan@aol.com. Meanwhile, I have a few recommendations for those unfamiliar with queer inclusive left thinking who might want to give it a shot:

Rod Ferguson, Aberrations in Black (introduction); Sophie Lewis, Full Surrogacy Now; Veronica Gago, Feminist International. Enjoy!