Andrea Dworkin Redux

We can appreciate Dworkin's contributions to feminism without erasing her contradictions or whitewashing her cruelty, can't we?

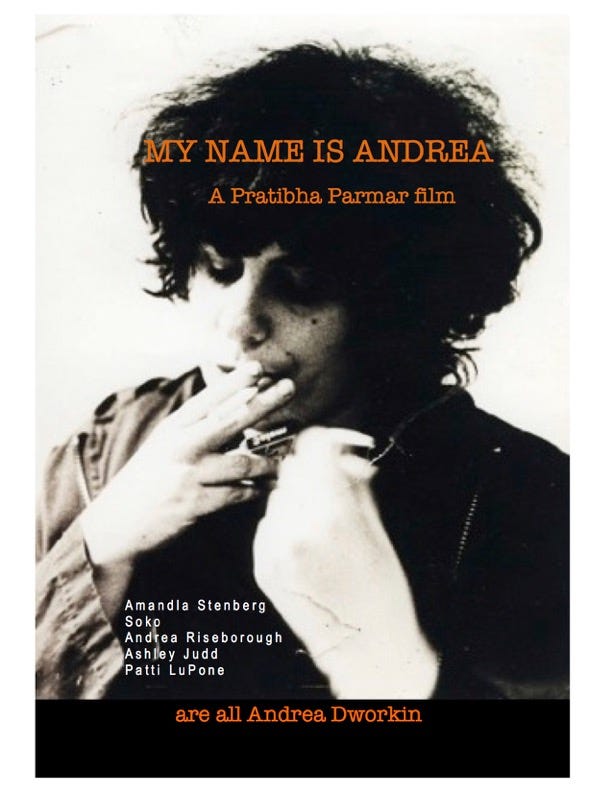

Yesterday, I was walking to Chelsea to see Pratibha Parmar’s new film about Andrea Dworkin, My Name Is Andrea, while listening to a podcast about psychoanalysis and politics. I had also just read Susie’s Bright’s post about You Tube’s astonishing termination of the entire Cornell Library account over the sexual content in lectures by Gayle Rubin and the On Our Backs editors and photographers. So I was fully primed to think about the film, and the ways it might deal with both Dworkin’s political legacy and the psychic life of sexual politics, in general.

My Name is Andrea is not a conventional, historical documentary—it is no criticism to say that it is not that. Rather, it is a literary/art film along the lines of Raoul Peck’s film about James Baldwin, I am Not Your Negro. In that film, Samuel L. Jackson reads from a partial manuscript by Baldwin, while we see archival footage of various scenes he describes. Baldwin’s text itself provides the historical context, the analysis, the lyricism of the film (though the film entirely excludes all reference to his sexuality). Parmar’s film uses actresses reading from and re-enacting scenes from Dworkin’s writing, shown alongside archival footage. The filmmaking itself is creative, moving, and powerful, like Dworkin’s prose. But My Name is Andrea falls down as the kind of literary/art film it aspires to be because Dworkin is not a contextualizing, self-aware or probing writer, as Baldwin is. Robin Morgan called her an Old Testament prophet for a reason—she is a righteous font of rage (in writing and in public, she is said to have been funny and gentle in private). There are a lot of good reasons for that rage, and it has a definite purpose and salutary impact. But as the film hews so closely to Andrea’s self-presentation, viewers do not get much of a sense of the changing historical context, the wide and deep personal roots (beyond gender injustice and sexual violence) or the political reception of that rage.

We get a good sense of Dworkin’s early political education, and her connections to the civil rights, anti-war and peace movements. We can track her evolution through harrowing experiences of sexual and domestic violence to her apotheosis as a feminist icon. But then everything goes vague. Her many abusive denunciations of feminists who disagreed with her (especially sex workers, bdsm practitioners and feminist pornographers)—including calling for Susie Bright’s assasination—are not included. There are about 5 minutes of film featuring Carole Vance and an anti-Sex Police demo, where the feminist critique of anti-porn politics is summarized. But viewers never get any kind of feel for the way Dworkin’s rages ranged across the political field, or why they did.

The feminist sex wars are, in a way, the least of the exclusions in the film though. There are no excerpts or enactments from some important later writings. These exclusions not only end up oversimplifying Dworkin’s political life, but they prevent viewers from seeing/hearing/feeling her full complex humanity. Two examples:

Her 2000 book Scapegoat: The Jews, Israel, and Women’s Liberation maps her struggle with her Jewish heritage and her relation to Israel. Her analysis is caught up in deep ambivalence—arguing that Israelis had no choice but to displace Palestinians, but also that the resulting occupation has been brutal. This is one of the few places where Dworkin tries to analyze brutality rather than only condemn it—the book is a fascinating departure on that front. A reader can feel her conflicts, struggles, and imperfect resolutions—for those she leans rather heavily on an almost ridiculously romantic notion of women’s solidarity across Israel/Palestine. Reading from that volume would have led the film out of hagiographic territory and into a more complex picture of Dworkin’s history with brutality, rage and ambivalence (much of her extended family was killed in the Holocaust). Martin Duberman’s 2020 book, Andrea Dworkin: The Feminist as Revolutionary, does a much better job of analysis on this terrain—terrain that the film does not tread.

The other piece of writing that the film does not touch is Dworkin’s rather alarming 2000 essay in The New Statesman, republished in The Guardian, “The Day I Was Drugged and Raped.” The events in this account, well analyzed by Susie Bright, and Martin Duberman among others, reveal Dworkin in the grip of terrible paranoia at the moment that her father died and her health began a steep decline. Even her closest friends and partners were deeply skeptical about the story she told in that essay. Aside from being a horrible tragedy, the events reveal the degree of projected rage, the remembered and reimagined pain and sorrow, that shaped Dworkin’s life and work. On the one hand Dworkin’s account of pervasive, endemic violence against women was and is reality-based, what she described reflected her experience and that of most (all?) women—she unearthed and expressed a rage based in deeply ingrained and ignored injustices at the root of the oppression of women. On the other hand, she tended to render these injustices as embedded in a universal binary—male violence and female suffering—that just does not describe the history of sexual violence (which is embedded in racial, class and other inequalities in complex relation to gender)—and to offer an explanation—pornography—that was reductive to the point of absurdity. The New Statesman essay, the events it describes and those that follow, show us something of the psychic mechanisms of disavowal, projection and paranoia that twisted and directed Dworkin’s rage in ways that were not always, well, productive. The precipitous decline of her mental and physical health subsequently tells us about the unprocessed pain and anguish that lay behind all that rage and in some sense just consumed her at the end of her life.

One thing the rage covered—ambivalence. Dworkin’s autobiographical fiction writing especially shows how ferociously she loved men, men’s writing and sex with men. She writes of doing sex work almost casually for money, of fucking enthusiastically, or teaching her eventually violent husband how to use rope, bite and otherwise engage in not exactly vanilla sex. She adores a whole string of male writers. She is comparatively little interested in women, as writers, thinkers or sex partners—she engages women in all these ways, but not with the same enormous passion. So when she turned, with good reason, to rage for all the harm and betrayal she experienced at the hands of men—she invented an apocalytic binary, with all that rage now turned outward. Women then appear as a flattened out set of undifferentiated victims, or as outraged activists behind her. What she could not countenance was women having fun with sex (as she once had), inventing forms of agency that bypassed her manichean world view, and criticizing her views. On those women who questioned her binary sexual politics, who wanted to play and create new sexual forms as well as overturn old oppressive ones—she turned her most devastating angry verbal assaults. I know because I was one of them. It was not fun. She was a terrible bully.

None of this complicating context—her ambivalent passion, her deep implication in some very abusive behavior of her own—none of that is in this film, which wants to bring Andrea back as a kind of prescient hero for the MeToo era. In part, she was that. There is much to reclaim and praise in her legacy—and there are others besides Parmar who have been doing that. But boy, she is SO complicated and messy, as most humans are. She was not just an unfairly maligned hero (though she was often unfairly maligned). She was both hurt and hurtful, a perceptive, even presient but often self-absorbed crusader who often did not *see* the people around her. Even her physical presence projected both a clear rejection of sexist aesthetic standards, and a kind of belligerently expressed self-hatred. And the film just can not (will not?) do justice to any of that……

(ps—I shall confess a very problemmatic association. While I was watching the film, Dworkin reminded me of Steve Bannon. There is NO political or moral equivalence! But…. the stark evidence of self-neglect in grooming and general appearance, the misery written into the face, the rage all directed outward with no self-awareness or insight, the manichean worldview, the rage at inequalities with no real class analysis, and more. I got chills, it was a creepy feeling. )

On one hand, this is precisely the kind of question that false-equivalency tendentiousness lives for.

On the other hand, this is precisely the reason it's impossible to just ignore or dismiss that reaction. I suppose the more powerful historically question might be, "Why was Andrea Dworkin an important public figure in terms of the positions she advocated considering that there were other figures who said what she said in ways that were both more responsible and in some ways more eloquent?" E.g., is she precisely one of those figures who calls into question our current understanding of online discourse as uniquely relying on an economy of attention that drives extreme rhetorical formulations of potentially less provocative positions? Was she someone who adroitly maneuvered for attention or influence by using impossible-to-ignore rhetoric, or was she someone produced by a discursive moment where that was the only way to make particular kinds of arguments and get any attention at all?

But the comparison to Baldwin (and Peck) is a good one; it's really hard (for me at least) to enshrine anyone who isn't at least someone open to self-reflection and self-doubt, whatever the political position. Before I get to the substantive evaluation of the content, that affect matters enormously to me as a sign of a politics of possibility--I just can't imagine anything that I think of as progressive arising out of a politics that disallows self-reflection and self-doubt.