Back from hiatus, and starting off the new year with a couple of links for your edification:

Here is Joanne Barker’s (Lenape) most excellent book launch for Red Scare: The State’s Indigenous Terrorist, with comments fron Audra Simpson (Mohawk) and Anne Spice (Tlingit), moderated by Hokulani Aikau (Kanaka Maoli)

And here is another treat! A new Thorny Acres story by Miss Anna McCarthy:

UNLIKE THE GOODWINS - Litro Magazine

And now to the business at hand:

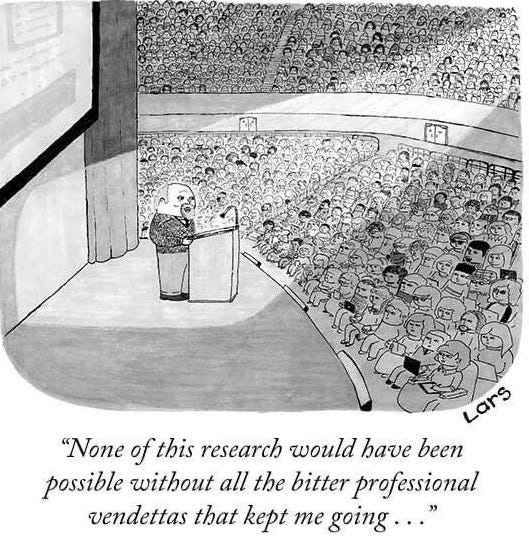

ACADEMIC AFFECT

When I teach graduate seminars, I outlaw the “piranha feed” process whereby the student with the most critical take on the assigned book wins, and anyone who praises it is dismissed as simple. I require the students to engage the books on their own terms first, outlining the authors’ aspirations and achievements before anyone is allowed to offer a critique. This approach has limited success. The socialization/“professionalization” of grad students exceeds the impact of any seminar. But the point is this—students who are trained to be sharply critical first and foremost have trouble finishing their own projects. They are paralyzed by the vision of their own work on the table for the prianha feed.

This is one of the primal scenes for the development of academic affect. Another is the conference paper, then job talk. Newly minted scholars present their work, usually defensively via reading a tightly edited script rather than talking to the actual live audience, and then are subjected to that first “this is really a comment more than a question.” The modes of attack in these settings differ by field. Henry Abelove (who taught in both history and literature departments at Wesleyan) once explained it to me: (a) Social scientists and historians are up against the trope of mastery, so the pointed question is about leaving out some crucial info (usually at the center of the questioner’s subsubfield), or for historians, about a problem of periodization (this really began much earlier than you say), (b) In the literary humanities, the reigning trope is difficulty, with density of expression and the right references valued, so the question is about quality of interpretation. The presenter can be (a) wrong, or (b) unsophisticated. Sure, some questioners are generous! But there is nearly always that takedown moment that generates defensiveness, anxiety, shame.

It’s not that academic affect is unique. Academics share a context with other kinds of writers—of fiction, general non-fiction, journalism—of a tight ego/work link (you are what you write), competitive envy and status obsession. They also share a corporate capitalist workplace with most other workers—with steep hierarchies, non-democratic decision-making, stark economic inequality, and invidious distinctions of race, class, gender, sexuality, ability, citizenship (including settler vs. indigenous) etc. The wide gaps among administrators at various levels, tenure track faculty at various ranks, contingent faculty and grad student workers, clerical and maintenance workers create injustice, brutality, precarity at the bottom and indifference at the top as intrinsic modes of daily being. So toxic affect is structured in ways not at all specific to universities and colleges.

But….there are some affective patterns that are especially prominent in academic settings. Some are positive! Curiosity, collaboration, a quest for understanding. Many are not. Anxiety leading to paralysis, isolation leading to depression, arrogance and contempt leading to withering condescension. There is a manufactured scarcity economy of smartness that leaves many clamoring for the top, only to be achieved by denigrating the competition. Then there’s the narcissism…..

One of the worst aspects of the academic affective economy, for me, is the requirement of passive aggression. There is a serious penalty for directness among colleagues, and a reward for the stab-in-the back approach to conflict. This is in part just bourgeois manners. But it is hard-wired into academic systems. I know of a professor who is a master at passive aggressive destruction. He piled unwanted tasks on a clerical worker who crossed him, put her office across the hall from the dept’s biggest harasser, and when she cracked under pressure and was fired, he praised her in a dept meeting as if he had nothing to do with it. So of course he became a dean. Few ever even noticed the long term pattern of passive aggression. On the other hand, the workers, graduate students and faculty I know who are direct when conflict arises have been routinely punished, gossiped about and shunned in a wide variety of official and unofficial ways.

I have my own set of ethical principles for navigating academic settings. (1) I don’t say anything behind a colleague’s back that I haven’t said directly to them, (2) I don’t denigrate faculty, staff or students to new arrivals in the dept/university (they shouldn’t be pressured to take sides in ancient disputes), and (3) I do not take my grudges out in professional settings (I have plenty of grudges! but I support my enemies for events and rewards based solely on relevant criteria). The big exception is I do gossip with my personal friends! But I keep it out of the department, university and profession in general—except in direct discussions about conflicts with the parties involved, which is where I get myself in trouble. This is not what everyone else does, of course. I have that colleague that many of us have who talks trash about me to every new faculty member, every grad student, and in every social situation.

But in addition to these shitty situations, I have also seen amazingly positive affective displays in academic contexts. These are mostly scenes of solidarity—rallying for the graduate student workers strike, support for contingent faculty and for staff unions, organizing for safety during the covid pandemic, and all kinds of individual as well as collective generosity. These, of course, are in no way particular to academia, but are the ways we all can respond to injustice, precarity, and general meanness in our workplaces—with cooperative solidarity, and even joy.

Note for Visitors and Subscribers: Please feel free to comment! And circulate….. I am using this substack to feel alive and connected during the pandemic, so the more connected, the better for me…. And subscriptions are FREE!

This post will resonate especially with international graduate students like myself. So much of the affective landscape you have described becomes a prerequisite for international students to embody if they want access to the Western university. Also, an addendum, would like to comment on enforced affective ephemera within academia. The criticality you speak of, must only last for the duration of a semester. Anything longer is deemed infeasible. We don’t know how to have a sustained relationship with our texts anymore.

I recall that my former advisor talked trash about other PhD students to me. It was not surprising at all that he also talked trash about me behind my back. The most difficult part, for me, is not the break of trust between the advisor and advisee, but to realize the fact that someone writing about 'justice,' 'power,' 'inequality' and so on treated others so differently from whatever value he asserted in his publications. (Just wanting to provide a little more context, I am also an international student + queer of color in the US.) Thank you for this post.